Suboart Magazine Nr 42; Artist Feature

Art Dog Istanbul; Between Dream and Reality

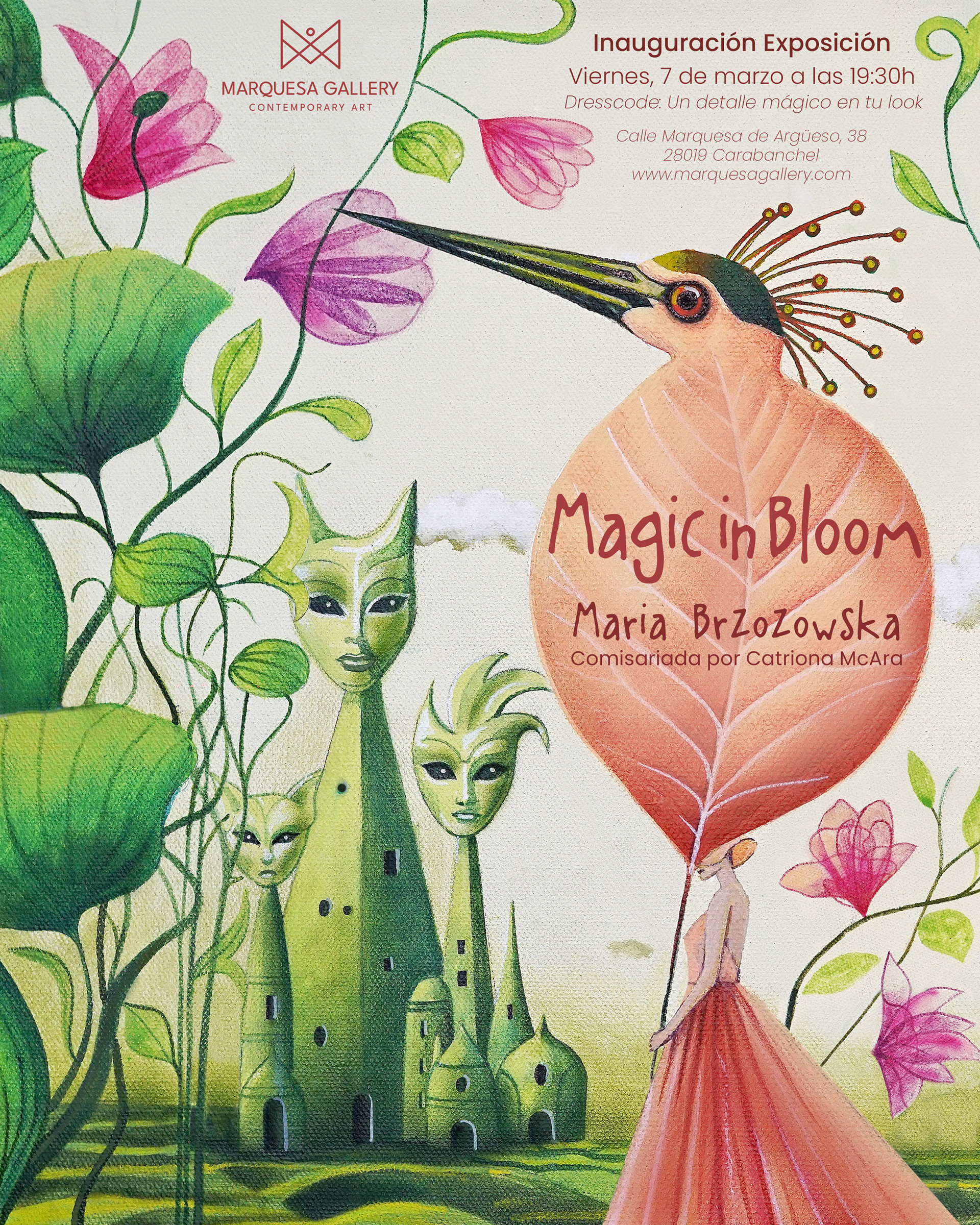

Solo Exhibition; "Magic in Bloom"

"Magic in Bloom" curated by Dr. Catriona McAra

📅 March 7th - June 17th

📍 Marquesa Gallery, Calle Marquesa de Argüeso 38, Carabanchel, Madrid

Marquesa Gallery Website | Opening Night Video | More About The Work

📅 March 7th - June 17th

📍 Marquesa Gallery, Calle Marquesa de Argüeso 38, Carabanchel, Madrid

Marquesa Gallery Website | Opening Night Video | More About The Work

MagicInBloom_MarquesaGallery_2025_PhotoByFernandoBorlan

MagicInBloom_MarquesaGallery_2025_PhotoByAndrésVargasLLano

MagicInBloom_MarquesaGallery_2025_PhotoByFernandoBorlan

MagicInBloom_MarquesaGallery_2025_PhotoByFernandoBorlan

MagicInBloom_MarquesaGallery_2025_PhotoByFernandoBorlan

MagicInBloom_MarquesaGallery_2025_PhotoByAndrésVargasLLano

MagicInBloom_MarquesaGallery_2025_PhotoByFernandoBorlan

MagicInBloom_MarquesaGallery_2025_PhotoByFernandoBorlan

MagicInBloom_MarquesaGallery_2025_PhotoByAndrésVargasLLano

Curatorial Text for "Magic in Bloom"

Gardens of Delight

“…the reader can hardly conceive my astonishment, to behold an island in the air…”

–Jonathan Swift (1726)

–Jonathan Swift (1726)

Maria Brzozowska (b.1992) is a secret genie. She works in meticulously detailed and exquisitely layered visual narratives inherited from Bosch, surrealism and their folkloric satellites. Her visual language offers a potpourri or magical confetti of recurrent motifs including owls and moths, masks and moons, doves and petals. From tulip to teapot, her make-believe dwellings are populated by jesters, nutcrackers and dancing princesses. Her latest solo exhibition, Magic in Bloom, invites us into an odyssey of feminine self-discovery through the numerous tiers of her dreamscapes with imagery that metamorphoses and surprises as she leads us through a series of portals, palaces and elaborate thresholds. As an English-educated, Polish-born painter, who has spent time absorbing the cultural heritage of Turkey, and is now based in Germany, such international coordinates lend her practice a mosaic of sources and rich array of reference points from puppet-theatre to picture-books.

The Garden of Earthly Delights (c.1500), the eponymous triptych by the Netherlandish painter Hieronymus Bosch, forms a backdrop to Brzozowska’s otherworldly domains. This connection is all the more relevant on this occasion given the proximity of Magic in Bloom to Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid. Brzozowska readily applies the lessons of Bosch especially his unusual sense of perspective and keen eye for detail, with giant birds, fish homunculi and seedpod contraptions that comingle with frolicking human figures in a seemingly infinite variety of visionary scenarios. Here, heaven and hell are both inspiring destinations, paradises and infernos which cater for a wide range of desires.

Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) offers another keystone for Brzozowska, particularly his floating island of Laputa in the land of Balnibarbi which seems ripe for creative cultivation. This moving land is defined by Swift as an irrational place where the learned inhabitants are very knowledgeable of mathematics and music. Laputa thus serves as a fertile site for Brzozowska’s enchanted gardens such as Seedling’s Dance, and her astute sense of precision which enables strange architecture formations and floral aberrations to flourish. Hers is a weird kind of natural history grounded in the fantastic.

The hallucinatory air castles in Brzozowska’s Lunaria’s Dream transport us towards twentieth century surrealism. As a fairy tale motif, the image of the floating castle in the sky became fixed in the surrealist imagination as a marvellous form of celestial navigation. While the movement’s leader, André Breton, was awaiting emigration to America during WWII, he wrote an extended poem called ‘Fata Morgana’ (1940), not necessarily as a whimsical vehicle for escapism but rather as a surrealist coping mechanism to deal with the reality at hand. Mythographer Marina Warner helpfully discusses the history of ‘Fata Morgana’ as a ‘meteorological wonder’ or castle-like apparitions in the clouds created by the bad fairy, Morgan le Fay, to lure sailors to their watery deaths. The ‘castle in the sky’ is a false image, a mirage or trompe l’oeil adopted by surrealism as an illusion which sits above or upon reality, like the child who enters a magical gateway into the world of story-time. Brzozowska’s Mother’s Seed and Marzanna’s Farewell are both reminiscent of a series of surrealist images. Belgian surrealist René Magritte’s dreamlike painting, Le château des Pyrénées (The Castle of the Pyrenees, 1959), carries such thoughts, the gravitational impossibility yet suspended disbelief of a weightless granite fortress soaring through the clouds. Meanwhile, surrealist Dorothea Tanning admired the commercial illustration of fellow American Maxfield Parrish, particularly the fleeting soap bubbles and contemplative mood of reverie in Air Castles (1904). One thinks also of Leonora Carrington’s wartime magic carpets and transatlantic flying vehicles as in La Chasse (The Hunt, 1942) and Tiburón (Shark, 1942), as natural alternatives to mechanical engineering.

Surrealism and the fairy tale chime and merge in all kinds of unique ways on Brzozowska’s canvases. I see her aesthetic embedded in the tradition of Carrington’s post-war lullaby paintings as well as the picture-books of her youth by Kay Nielsen and Heath Robinson. Carrington’s The Kitchen Garden on the Eyot (1946) and Again, the Gemini are in the Orchard (1947), include domestic details, a tiny apple tree and a splendid cockerel, preparing the child for sleep within the safe confines of a soothing landscape. We would be wise to recall how necessary such imagery is in enabling us to dream meaningfully during troubled times. Solomon Adler describes Carrington’s walled garden as “a grand metaphor for creation.” An eyot is a river island, an idea which appeals to Brzozowska’s miniature dreamscapes too. Brzozowska responds with her rose-tinted Garden Spirits, its magenta leaves carefully pruned, with costumed triplets equipped for symbolic action.

Max Ernst’s lush painting, La Joie de Vivre (The Joy of Life, 1936), also pre-empts Brzozowska’s vegetal surreal in Kingdom of Leaves and Melancholia’s Garden. Ernst’s Thumbelina painting celebrates the jungle world of the undergrowth with insects as large as monsters. A miniature sense of scale is integral to Brzozowska’s emerald cities too, her angelic blossoms dispelling everyday phobias. Susan Stewart reminds us of our nostalgia for containment:

The clumsiness of Gulliver, the ways in which new surfaces of his body erupt as he approaches the Lilliputian world, is the clumsiness of the dreamer who approaches the dollhouse. All senses must be reduced to the visual…

For what felt like the longest time, there was a critical allergy to such delicate imagery, an anxiety around the free reign of feminine story-time. Yet, feminist literary custodian, Kate Bernheimer, has long defended the genre:

I sometimes even hear fairy-tale motifs automatically dismissed as feminist clichés, reflecting a serious misapprehension of the form's intricate political history. Of course, it is no surprise that fairy tales are often undermined and exploited, for they have a long association with women, children, and animals, and the things that they live with, those underlings of the natural world: old wives and their ovens, wolf-girls and their spindles.

Tanning also felt her visual narratives were frequently misread by critics for being “dainty feminine fantasies…bristling with…symbols.” When looking at Brzozowska’s own symbolic repertoire, one might be reminded of the giant, wilting sunflower in Tanning’s dollhouse painting, Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (A Little Night Music, 1943), or the angel wing hiding inside the strange structure of Moeurs Espagnoles (Spanish Manners, 1943). Tanning’s self-portrait Birthday (1942) also includes a skirt of tangled branches with faerie figures blooming between the lush vines. Surrealism offers Brzozowska a marvellous kind of family tree with multiple sources from which to draw.

Frida Kahlo’s tiny votive paintings and Remedios Varo’s alchemical obsessions are also present in Brzozowska’s toolkit. Kahlo’s Roots (1943), like Gulliver in Lilliput, coil and embed the artist’s body in the scorched landscape, while Kahlo’s numerous self-portraits inform Brzozowska’s Melancholia tondos. Elsewhere, Varo’s Creation of the Birds (1957) haunts the feathered realm of Brzozowska’s Night Owl’s Lullaby and Floral Alchemist. Finally, Bridget Bate Tichenor’s distinctive visual narratives, such as the towering mask formation of Seller of Miracles (1967), and Leonor Fini’s curious disguises and mythological lionesses, such as Little Hermit Sphinx (1948), are both echoed in the epic circus of Brzozowska’s Venetian Dream.

From the bizarre to the bazaar. After surrealism, came the storytelling frames within frames of Italian folklorist, Italo Calvino. His novel, Invisible Cities (1972), offers a labyrinthine and touristic experience, a guidebook to Brzozowska’s Nectar City and beyond:

At the end of three days, moving southward, you come upon Anastasia, a city with concentric canals watering it and kites flying over it. I should now list the wares that can profitably be bought here: agate, onyx, chrysoprase, and other varieties of chalcedony… sprinkled with much sweet marjoram.

Like a zodiac, we might read each of Brzozowska’s latest paintings as Calvino’s mythic metropolises. This goes for the ornamental Lunar Whispers and hanging mobile moon in Dream Cave. If writing is a form of planting seeds, then Brzozowska’s painting is a practice of fantasy cultivation, a resplendent mode of visual horticulture and illusionary architecture, metamorphosing between wishes, provoking the viewer to daydream.

Dr. Catriona McAra

Art Historian | Curator | Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Art History at the University of Aberdeen

Dr. Catriona McAra

Art Historian | Curator | Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Art History at the University of Aberdeen

1. Jonathan Swift, Gulliver's Travels, ed. Colin McKelvie (Belfast: Appletree Press Ltd., 1976), 140.

2. Marina Warner, Phantasmagoria: Spirit Visions, Metaphors, and Media into the Twenty-first Century (Oxford University Press, 2006), 101.

3. See my 'Leonora Carrington: Wild Card,' The Space Between, volume 14 (2018): https://scalar.usc.edu/works/the-space-between-literature-and-culture-1914-1945/vol14_2018_mcara Accessed 25 February 2025

4. Carrington's technique draws on 'the golden age' of children's picture book illustration, see my 'Leonora Carrington and Children's Literature,' Gramarye: Journal of the Sussex Center for Folklore, Fairy Tales and Fantasy, issue 12 (Winter 2017), 36-45. See also, Rodney Engen, The Age of Enchantment: Beardsley, Dulac and Their Contemporaries 1890-1930 (London: Scala Publishers Ltd., 2007), 98.

5. Solomon Adler, 'Leonora Carrington: The Kitchen Garden on the Eyot,' SFMoMA (December 2020): https://www.sfmoma.org/essay/leonora-carrington-the-kitchen-garden-on-the-eyot-1946/

6. Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), 67.

7. Kate Bernheimer, 'This Rapturous Form,' Marvels and Tales, 20:1 (2006): 82-83.

8. Dorothea Tanning, Between Lives: An Artist and Her World (London and New York: WW Norton and Co., 2001), 336.

9. Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities (London: Vintage, 2023), 10.

2. Marina Warner, Phantasmagoria: Spirit Visions, Metaphors, and Media into the Twenty-first Century (Oxford University Press, 2006), 101.

3. See my 'Leonora Carrington: Wild Card,' The Space Between, volume 14 (2018): https://scalar.usc.edu/works/the-space-between-literature-and-culture-1914-1945/vol14_2018_mcara Accessed 25 February 2025

4. Carrington's technique draws on 'the golden age' of children's picture book illustration, see my 'Leonora Carrington and Children's Literature,' Gramarye: Journal of the Sussex Center for Folklore, Fairy Tales and Fantasy, issue 12 (Winter 2017), 36-45. See also, Rodney Engen, The Age of Enchantment: Beardsley, Dulac and Their Contemporaries 1890-1930 (London: Scala Publishers Ltd., 2007), 98.

5. Solomon Adler, 'Leonora Carrington: The Kitchen Garden on the Eyot,' SFMoMA (December 2020): https://www.sfmoma.org/essay/leonora-carrington-the-kitchen-garden-on-the-eyot-1946/

6. Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), 67.

7. Kate Bernheimer, 'This Rapturous Form,' Marvels and Tales, 20:1 (2006): 82-83.

8. Dorothea Tanning, Between Lives: An Artist and Her World (London and New York: WW Norton and Co., 2001), 336.

9. Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities (London: Vintage, 2023), 10.

March 7th 2025

"Magic in Bloom"

📅 Friday, March 7th

🕢 7:30 PM – 11:00 PM

📍 Marquesa Gallery, Calle Marquesa de Argüeso 38, Carabanchel, Madrid

📅 Friday, March 7th

🕢 7:30 PM – 11:00 PM

📍 Marquesa Gallery, Calle Marquesa de Argüeso 38, Carabanchel, Madrid

More Information: marquesagallery.com

December 2024

Arte Laguna Prize Exhibition

"A Venetian Dream" was featured in the Arte Laguna Prize exhibition at the Arsenale Nord in Venice, an international celebration of contemporary art.

"A Venetian Dream" was featured in the Arte Laguna Prize exhibition at the Arsenale Nord in Venice, an international celebration of contemporary art.

Finalist: Arte Laguna Prize

Selected as a finalist for the prestigious Arte Laguna Prize in the Painting category.

Selected as a finalist for the prestigious Arte Laguna Prize in the Painting category.

October 2024

Marquesa Gallery

New collaboration with Marquesa Gallery in Madrid, Spain with work showcased as part of the gallery's opening group exhibition.

New collaboration with Marquesa Gallery in Madrid, Spain with work showcased as part of the gallery's opening group exhibition.